As Richard Nixon stood before the nation on January 20, 1969, to take the oath of office, he stood before a country rife with division and turmoil. In his address, he turned to another president who knew the strains of division, Abraham Lincoln. President Lincoln closed his first inaugural address on March 4, 1861, with the words:

“We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearth-stone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

In his first remarks to Americans as president, Richard Nixon echoed Lincoln’s call to look to the virtues within ourselves:

To a crisis of the spirit, we need an answer of the spirit.

And to find that answer, we need only look within ourselves.

When we listen to “the better angels of our nature,” we find that they celebrate the simple things, the basic things–such as goodness, decency, love, kindness.

Greatness comes in simple trappings. The simple things are the ones most needed today if we are to surmount what divides us, and cement what unites us.

To lower our voices would be a simple thing.

In these difficult years, America has suffered from a fever of words; from inflated rhetoric that promises more than it can deliver; from angry rhetoric that fans discontents into hatreds; from bombastic rhetoric that postures instead of persuading.

We cannot learn from one another until we stop shouting at one another–until we speak quietly enough so that our words can be heard as well as our voices.

President Nixon addressed the nation as it was still reeling from the previous year, which included riots, unrest, and the assassinations of two leaders within two months of each other: civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy.

Writing in his Memoirs, President Nixon shared his reaction to the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy:

“Bobby Kennedy and I were political antagonists, representing wholly different constituencies and philosophies. There was nothing similar about our beliefs or styles. But we shared, as all politicians do, membership in an uncharted club of those who devote their energies and themselves to public life and public service. I was, as I had always been, fatalistic about danger. But I was saddened and appalled by such human waste.”

Another line from that 1969 inaugural address is etched on President Nixon’s unadorned gravestone, “The greatest honor history can bestow is the title of peacemaker.” Richard Nixon knew firsthand the weight of peace. He served as a Navy lieutenant in World War II and as commander-in-chief during Vietnam. His life spanned most of the twentieth century, a century torn by war on a global scale. Pragmatic to the core—his leadership style defined conservative realism—yet he knew the driving goal had to be peace.

Throughout his public service, Nixon practiced peace in the arena. As a young congressman, he made his name as a staunch anti-Communist, yet when he landed in China he extended his hand to Premier Zhou Enlai, symbolizing the opening of China to the West. He lost one of the closest presidential elections in U.S. history to John F. Kennedy, yet accepted Kennedy’s invitation to consult after the Bay of Pigs. After resigning the presidency, he continued to serve, advising leaders of both parties—including, in his final months, a president from the other side of the aisle. For Nixon, peace meant engaging with those of different beliefs, putting country above party, and contributing as long as one had strength to give.

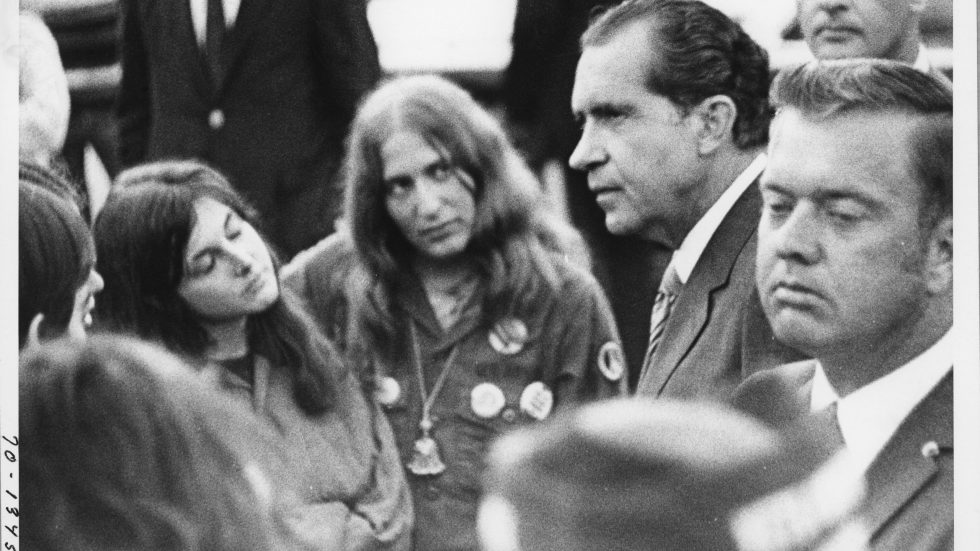

In what Dwight Chapin, aide to President Nixon, describes as “one of the more consequential events of the Nixon presidency,” President Nixon went to the Lincoln Memorial and engaged with young people who were there protesting the war in Vietnam. Describing the encounter, President Nixon wrote, “…I realized that most of them would not agree with my position, but I hoped they would not allow their disagreement to lead them to fail to give us a hearing on some other issues where we might agree.”

This practice of hearing the other side and finding common ground was established early in President Nixon’s life. In his Memoirs, he talks about learning debate skills from his father. He went on to win competitions on his college debate team, reflecting, “Because of the way our college debates were organized, the team had to be prepared to argue either side of a question. This sort of exercise turned out to be a healthy antidote to certainty, and a good lesson in seeing the other person’s point of view.” Through a half-century of being in the political arena—serving as congressman, senator, vice president, president, and elder statesman—that foundational view of debate remained core to how he interacted with others, from advisors and world leaders to allies and those in the opposition.

Thirty-five years ago, when describing the mission of the Nixon Library, President Nixon said that he did not want a monument to one man or a place where people only study the policies of his administration. Rather, he said, “I hope the Nixon Library and Birthplace will be different—a vital place of discovery and rediscovery, of investigation, of study, debate and analysis.”

Today, the Nixon Foundation continues that mission by hosting speakers to foster discussion and debate, curating exhibitions that educate and inform, and advancing civics education to pass on the promise of our Founders to the next generation. These efforts reflect the enduring spirit of Richard Nixon’s vision.

As President Nixon was making plans to celebrate the country’s bicentennial, he looked to the country’s founders, calling for a renewal of the Spirit of ‘76. Fifty years later, as we prepare to celebrate another milestone birthday, the Nixon Foundation echoes Nixon’s call from his acceptance remarks on the Republican presidential nomination in 1968 to “apply the lessons of the American Revolution to our present problem.” Looking to those shared virtues that brought unity to thirteen colonies, those “better angels” can bring unity not in spite of our differences but because of them.